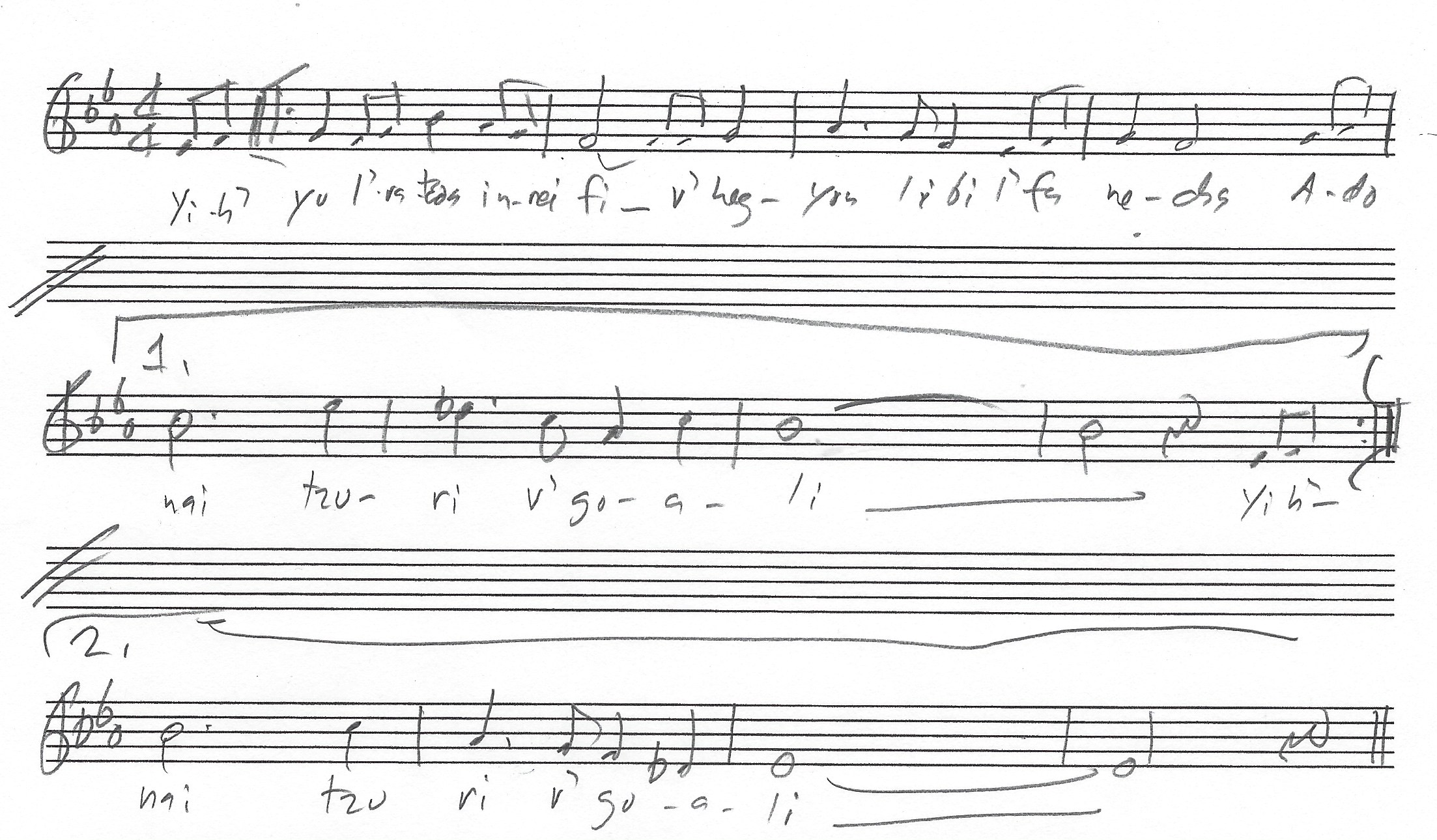

One week from today, HaZamir:The International Jewish Teen Choir, will perform at Carnegie Hall in New York City. One of my choral pieces, Netzach Yisrael will be part of the program.

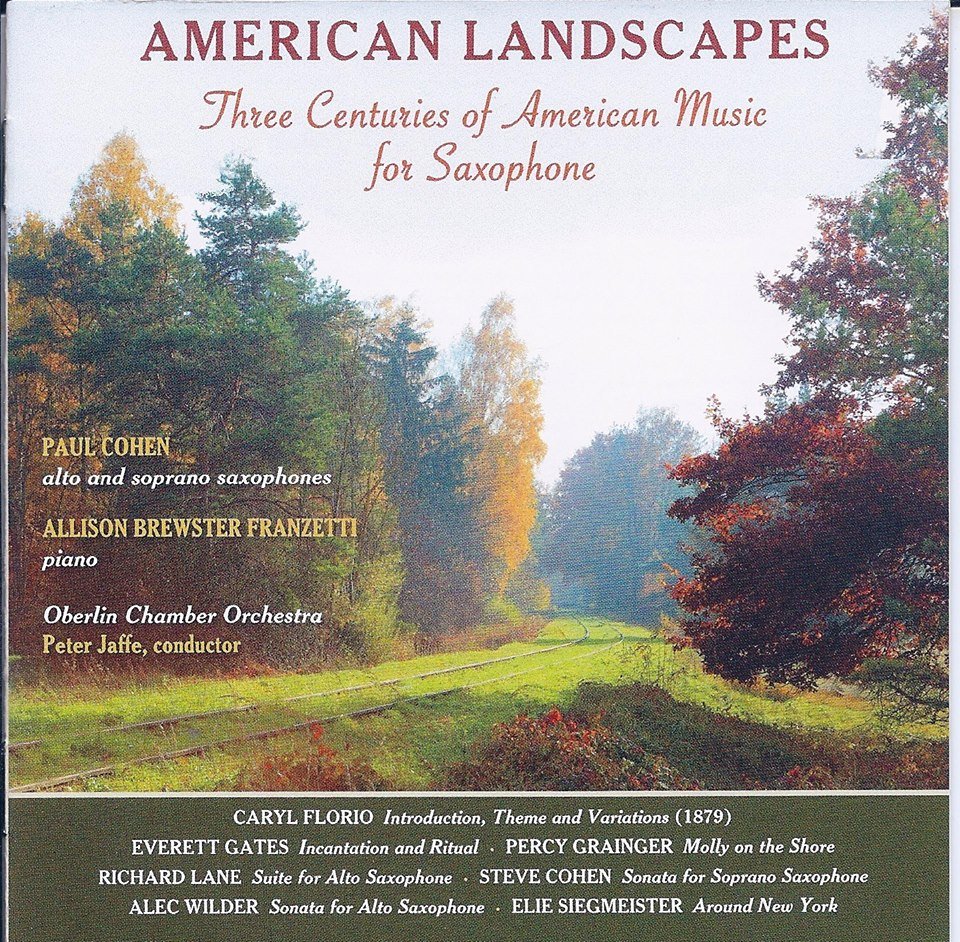

Carnegie Hall is one of the world’s greatest concert venues, and I have a long and very happy relationship with it. My choral work has been performed there many times, my orchestrations have been played there by the New York Pops and the New York Choral Society, and I’ve sung onstage there in the bass section of the Zamir Chorale.

Over the years, I’ve noticed that having my work performed at Carnegie Hall never gets old; it’s always a thrill and an honor.

My first association with Carnegie Hall was unusual, which explains why the word “Debut” is in quotation marks in the title of this blog entry.

During my career as a freelance musician, a lot of my work came from ads I placed in various trade papers. I got calls to coach and accompany singers, as well as transcribing music from tape recordings for songwriters who could not do their own notation.

Many of my clients were elderly people who had retired from work, and were now free to follow their long-deferred dreams of doing something in music. More often than not, I seemed to function more as an occupational therapist that as a musician.

One of my clients - I forget his name - taught in the NYC Public Schools, and after he retired he started writing short pieces for orchestra. I was hired to recopy his scores and to extract parts for the orchestra players. His work was not flashy, but it had a kind of homespun charm to it.

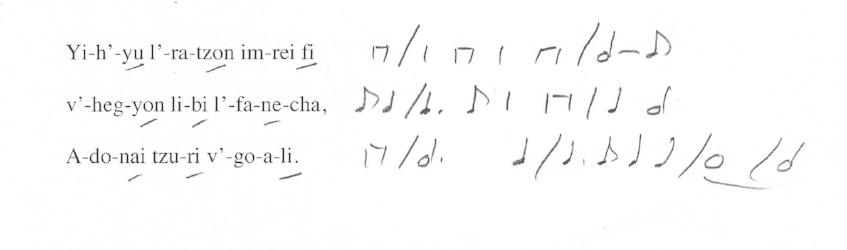

One of his pieces was a set of three “Hebraic Moods,” each about a minute long. The last movement was in the style of a folk dance. The movement ended with a solo bassoon repeating the melody and then drifting off into nothingness.

I suggested that my client should add a “button” at the end; a “button” being a short chord for the entire orchestra, to serve as a cue to the audience that the piece was over. This would avoid a potentially awkward silence after the piece was over.

My client didn’t think much of my idea, so I let it pass.

A few days later, my client called me on the telephone. He had sent the piece to the conductor of the Local 802 Senior Concert Orchestra. and the conductor liked the piece well enough to consider adding it to the program of a free concert the orchestra was to give at Carnegie Hall. The conductor, however, insisted that my client add a “button” at the end, and gave as his reason, the same argument I had made about the ending.

I resisted the urge to say “I told you so!”

My client asked me to add the button. I had all the materials, score and parts, in a folder at my office, so I added the “button,” a nice assertive D major chord, in the score in the score and parts.

These materials were printed, bound, and sent to the orchestra’s librarian.

I was given a pair of tickets to the concert, and I went with a friend of mine.

The piece worked very nicely, and the “button” did just what “buttons” are supposed to do.

I turned to my friend and said, “You hear that nice chord at the end? That’s mine!”

Eventually, other pieces would be heard at Carnegie where all the notes were mine.

Everybody’s got to start somewhere, and this humble beginning was my foot in the door at Carnegie Hall.