Right off the bat, my Sonata for Soprano Saxophone and Piano is a piece, not a song. However, I like the alliteration of Story and Song, so let’s let it stand.

I wrote the Soprano Sax Sonata in the later part of 2001, and I finished it in early 2002.

The story starts a long time before that, however.

While I was a freshman at Manhattan School of Music, in 1972, I heard saxophonist Paul Cohen (no relation) play in a recital. Paul was studying for a Masters degree at the time. I had never heard sax playing like this; unlike the sax-playing I had heard in jazz and rock, Paul’s sound was sweet and pure, like a classically-trained singer, and he was able to produce the entire gamut of dynamics, from ppp to fff.

I decided that I’d like to write something for Paul, and Paul was enthusiastically in favor of this. (Paul is a great evangelist for saxophone music, and I remember that when we were first introduced, by a mutual friend, his first words to me were “What have you written for saxophone?”)

I made it my business to have a saxophone in the band for an off-off Broadway musical (“New York Flesh & Fantasy”) I wrote in 1976. This was followed by a Quintet for Alto Saxophone and Strings (1978) and my first Saxophone Quartet (1980).

By the time I wrote Saxophone Quartet Nº 2 (1998), Paul was teaching saxophone at Manhattan School of Music. When I showed him the score, Paul assigned the piece to four of his graduate students. The leader of this group was James Noyes. While the group prepared to give the piece’s premiere, James always had questions for me, and these were smart questions that required me to dig deep in order to answer them.

Sax Quartet Nº 2 was premiered in April, 1998. The group stayed together as the Surge Saxophone Quartet, and managed to win an Artists International award that gave them to perform at Carnegie Recital Hall.

After all of this, James felt comfortable enough to make a suggestion, and he said to me, “Steve, you should write a piece for soprano saxophone. All of the recital literature is for alto sax. If you wrote a good piece for soprano, you. would get a LOT of performances!” I saw the wisdom of James’s suggestion, but I did not act upon it right away.

Fast-forward to 2001. The events of September 11, 2001 had a devastating effect on New York City, both emotionally and financially. Tourism stopped, and the theater business suffered terribly. As I was making the bulk of my living as a copyist, proofreader, and sometimes orchestrator of Broadway musicals, I found myself out of work, and very depressed.

I stayed depressed for quite a while, and then I remembered that James Noyes wanted me to write something! I began to think about a soprano sax piece. Thoughts of what to write and how to write it took my mind off the gloom around me, and it gave me a sense of purpose.

Sometimes I’ll begin a new piece with all-new ideas. More often, I begin by taking inventory of ideas I just happen to have lying around in my brain, gathering dust. (In the world of musical theater, such things are referred to as “trunk tunes.”)

Years earlier, I had thought of writing a flute sonata, but the opening I had reminded me so much of the Poulenc Sonata, that I was never able to make much headway with it. But, it occurred to me, there probably wasn’t such a piece for soprano sax. So I took my flute sonata opening, changed the key from E minor down to B-flat minor to put the soprano sax in a better range. Things began to flow once I had made this change.

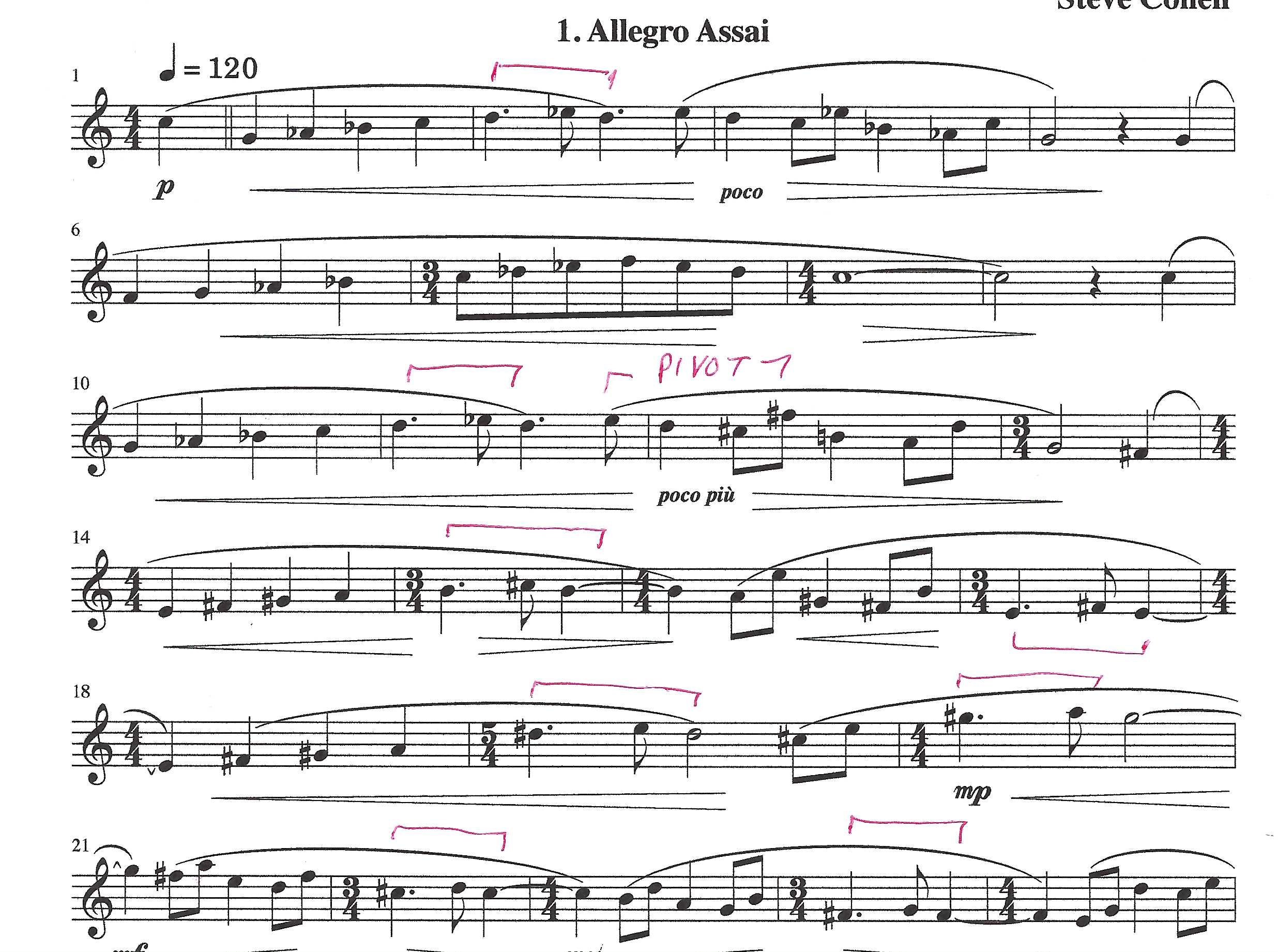

MOVEMENT 1

The opening theme of the first movement rises to a high note that serves as a pivotal point to go to other harmonic regions. The red marks in the photo show what I mean:

I knew that later on in the movement, I’d want to get back to the main theme by way of the pivot-point. That would be a startling, dramatic way of getting into the recap section.

So that, by me, is a very satisfying arrival point. But those figures that lead up to it four measures before the arrival point, what are those?

After some thought, I realized that the figures that lead to the recap could be the basis of the secondary motive. Working backwards, I came up with a melody that used those figures as its basis.

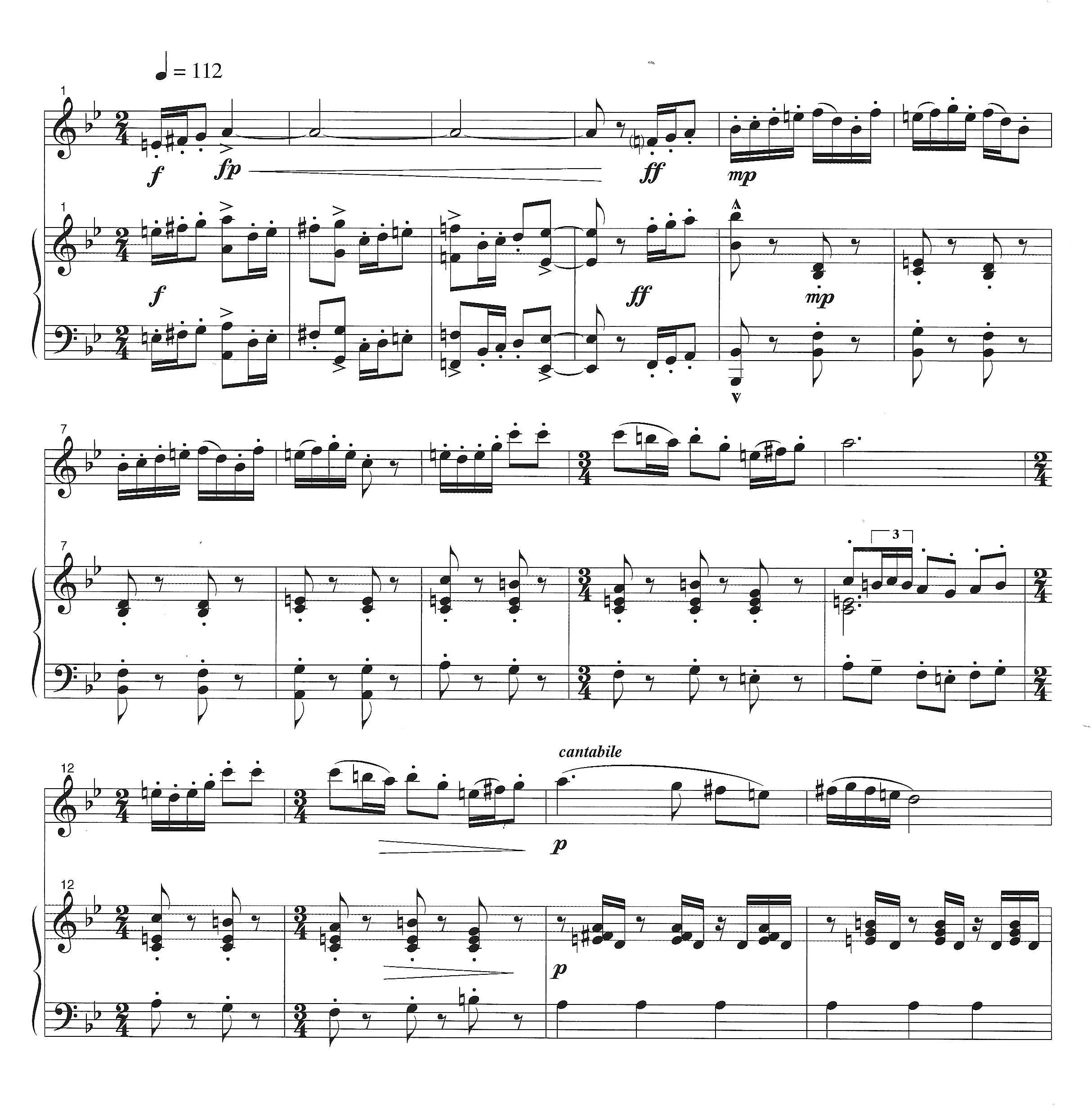

Movement 2

Towards the end of 2001, I often had trouble sleeping. One night, around 4 AM, some musical ideas came to me. I got up to write them down, and every now and then I needed to look at a piano keyboard, but I wouldn’t allow myself to play it, lest I disturb the rest of the sleeping household. I held my hand over the keys, sounded out the notes silently in my head, and jotted them down on manuscript paper. In the morning, I looked at what I’d written, played it on the piano, this time for real, and I decided that what I had was useable.

The idea led to other ideas, and in a few hours I had lots of material to use.

This would become the basis for Movement 2, a slow, bluesy piece in E-flat Major.

In structure, it’s basically an AABA song form. I had the idea of starting the first A in the soprano sax’s lowest register, going up an octave to the middle range for the second A, and, after the B (Bridge) section, using the highest range for the third and final A section.

While I was working on the second movement, I learned that. one of my musical heroes, arranger Ralph Burns had passed away. I never had the pleasure of meeting Mr. Burns, but having copied or proofread several musicals he orchestrated, I felt as if I knew him. Burns had started in big-band jazz, played piano for Woody Herman and contributed many scores to the band’s repertoire. Later on, he started orchestrating Broadway shows, including Funny Girl, Sweet Charity, and Chicago. Burns brought a jazz sensibility to Broadway musicals, and they’ve never been the same since. It seemed fitting to be writing something like the blues at the time, and I decided to dedicate the movement in memory of Ralph Burns.

Movement 3

After the second movement’s “dark night of the soul” atmosphere, it was time for a total change of pace and mood.

I repurposed a short piece I wrote at the age of 17, originally for oboe and piano. It was sprightly and cheeky, and centered mostly around the Lydian mode (basically a major scale but with a raised 4th step).

The first 1’ 30” of the movement come from that youthful oboe piece, but the melody that follows is (was) new material, written by my 47-year-old self. It’s quite a contrast.

The music for Movement 3 doesn’t require much explanation; it makes its point all by itself.

One harmonic trick seems worth mentioning.

The main theme starts in B-flat, but in its the second half, we find ourselves suddenly in D Major.

Towards the end, I wanted that D Major section of the theme to come back in B-flat, which is the home key for the movement. In order to accomplish that, the first part of that tune would need to be in G-flat. Once in the home key, I combine the lyrical middle-section melody over the opening material, which wraps things up nicely, if I do say so myself!

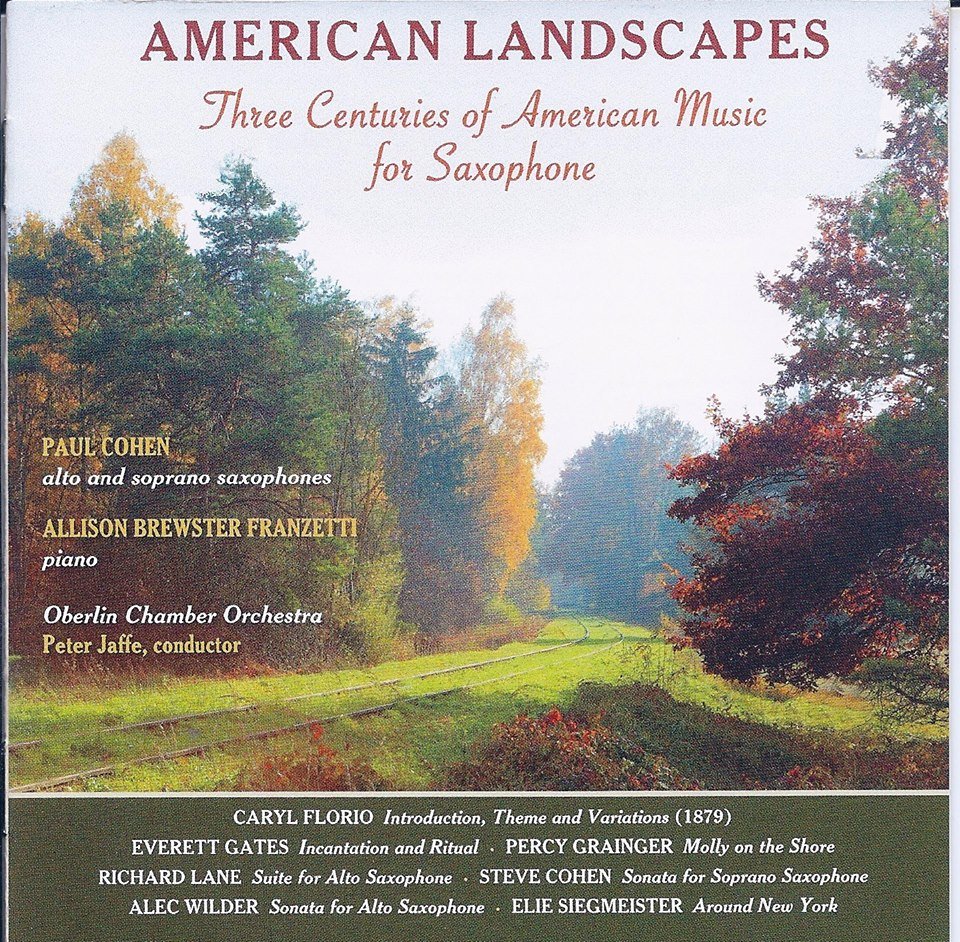

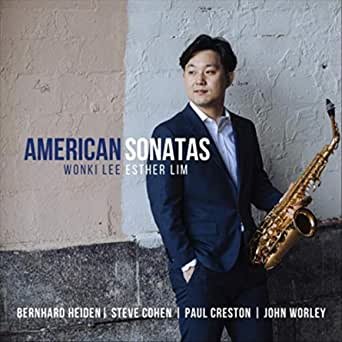

I must say, James Noyes was right! This Soprano Sax Sonata has garnered many performances, all around the world, and has been recorded on three different CDs.

See the RECORDINGS page for details

The moral to this story is this: If you’re a composer, you would do well to listen to performers when they tell you about the sort of piece they’d like to perform, but they can’t find it. Once you’ve identified a need, you can find a way to fill that need, and the world (part of it, at least) will beat a path to your door. Leave a light on for them!